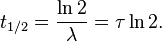

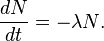

Thus it is evident that t1/2 of an element does not depend on the initial amount of radioactive element but depends on the value of l.

The t1/2 of a particular radioactive isotope is a characteristic constant of that isotope. Values of t1/2range from millions of yearsThe disintegration rate is also referred to as activity. The SI unit of radioactivity is becquerel (Bq) named after Antoine Becquerel, which is equal to one disintegration per second. The older unit, curie, named after Marie Curie is still used, One Curie (Ci) is defined as the amount of radioactive isotope that give 3.7 x 1010 disintegrations per second. This is the activity associated with 1g of radium-225 with half - life of 1600 years).

Thus 1 Ci = 3.7 x 1010 disintegration s-1= 3.7 x 1010 Bq.

.

.

The applet lists a "halflife" for each radioactive isotope. What does that mean?

The applet lists a "halflife" for each radioactive isotope. What does that mean?

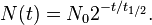

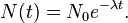

Hmmm...so a lot of decays happen really fast when there are lots of atoms, and then things slow down when there aren't so many. The halflife is always the same, but the half gets smaller and smaller.

Hmmm...so a lot of decays happen really fast when there are lots of atoms, and then things slow down when there aren't so many. The halflife is always the same, but the half gets smaller and smaller.  That's exactly right. Here's another applet that illustrates radioactive decay in action.

That's exactly right. Here's another applet that illustrates radioactive decay in action.  Notice how the decays are fast and furious at the beginning and slow down over time; you can see this both from the color changes in the top window and from the graph.

Notice how the decays are fast and furious at the beginning and slow down over time; you can see this both from the color changes in the top window and from the graph. What happens when an atom doesn't have enoughneutrons to be stable?

What happens when an atom doesn't have enoughneutrons to be stable?  That's the case with beryllium 7, 7Be4. Click on it in the applet and see what happens.

That's the case with beryllium 7, 7Be4. Click on it in the applet and see what happens.  Right...so instead you emit a positron--a particle that's just like an electron except that it has opposite electric charge. In nuclear reactions, positrons are written this way: 0e1.

Right...so instead you emit a positron--a particle that's just like an electron except that it has opposite electric charge. In nuclear reactions, positrons are written this way: 0e1.  So the reaction looks like this:

So the reaction looks like this: Good. The applet will show you many other decays that produce either electrons or positrons; it's easy to tell which, by the "direction" in which the decay moves. Sometimes it even takes more than one decay to arrive at a stable isotope; try 18Ne or 21O, for example.

Good. The applet will show you many other decays that produce either electrons or positrons; it's easy to tell which, by the "direction" in which the decay moves. Sometimes it even takes more than one decay to arrive at a stable isotope; try 18Ne or 21O, for example.  So all radioactive isotopes decay by giving off either electrons or positrons?

So all radioactive isotopes decay by giving off either electrons or positrons?

The neutron turns into a proton! 3H1 becomes 3He2.

The neutron turns into a proton! 3H1 becomes 3He2.  Hydrogen has only one proton, and helium has two, so you'd end up with twice as much positive charge as you started with. How do you get around that?

Hydrogen has only one proton, and helium has two, so you'd end up with twice as much positive charge as you started with. How do you get around that?

No; there are "preferred" combinations of neutrons and protons, at which the forces holding nuclei together seem to balance best. Light elements tend to have about as many neutrons as protons; heavy elements apparently need more neutrons than protons in order to stick together. Atoms with a few too many neutrons, or not quite enough, can sometimes exist for a while, but they're

No; there are "preferred" combinations of neutrons and protons, at which the forces holding nuclei together seem to balance best. Light elements tend to have about as many neutrons as protons; heavy elements apparently need more neutrons than protons in order to stick together. Atoms with a few too many neutrons, or not quite enough, can sometimes exist for a while, but they're

Well, yes, in a way. Unstable atoms areradioactive: their nuclei change or decay by spitting out radiation, in the form of particles or electromagnetic waves.

Well, yes, in a way. Unstable atoms areradioactive: their nuclei change or decay by spitting out radiation, in the form of particles or electromagnetic waves.